Trusted Third Parties and Privacy

Over the last year I have read many privacy policies. We are totally clued up on privacy policies – after all, we run an online service which enables people to send millions of emails, and how we handle that data is critical to our offering, so we want them to know how we operate.

Privacy policies are frequently horribly verbose, ambiguous, and vague. Many exist solely to (mostly ineffectively) tick some compliance check box, and do not accurately reflect internal culture and behaviour – on the contrary, they often exist only to confuse, muddle, and obfuscate true actions, and hide excessive sharing and third-party involvement.

One dead giveaway is the appearance of the word “may”, in phrases like “we may share your data with trusted third parties”, without actually saying who they are. This is often accompanied by a suggestion that you should read the policies of the third parties, so disclaiming responsibility for what they are allowing their suppliers to do. This lack of transparency suggests two things – either they know who they are sharing data with and don’t want to tell you, or they don’t actually know who they are sharing data with, but are happy to take any income that it generates anyway.

The hope seems to be that enough vague and ambiguous language, describing nebulous, hand-wavy policies written in long-winded “legalese” style will be sufficient to bamboozle users into being duped that everything is cool and they shouldn’t worry their pretty little heads about it.

In light of this, I have become more interested in the term “trusted third parties”. What does that actually mean?

A trusted third party is typically an external service that provides some kind of added value to the site’s host. This might be telling them demographic information about the visitor like their age and country that allows they to target advertising and content to suit them. This in itself is not necessarily bad, however, the way it is implemented usually is. All too often it involves oversharing (sending excessive, identifiable data), and a lack of transparency (little or no information about how it is used, and how the subject can do anything about it).

These trusted third parties are often located in countries with data laws in complete opposition to ours, or simply don’t exist. The EU has an historic and growing culture of privacy, and this often conflicts with countries where personal data is a commodity to be mined for value at every opportunity, for motives good or bad. These approaches are diametrically opposed; However many words are written in a policy, these two positions are impossible to reconcile. Personal data should be handled like a safe deposit box; It can be moved around securely, and only opened by those that truly need access to it, and can prove it. In practice, it’s more like a dropped deck of cards – a mess, and everyone can see everything.

Now, these trusted third parties are companies like any other, made up of people and computers. So who has access to the data? Who runs the security and maintenance of the computers? Where are the computers physically located? How do backup procedures work? To grant these third parties that valued “trusted” label, we really need to have the answers to these questions but herein lies a problem: you have no way of knowing whether this is actually being done in compliance with your wishes, or even the law.

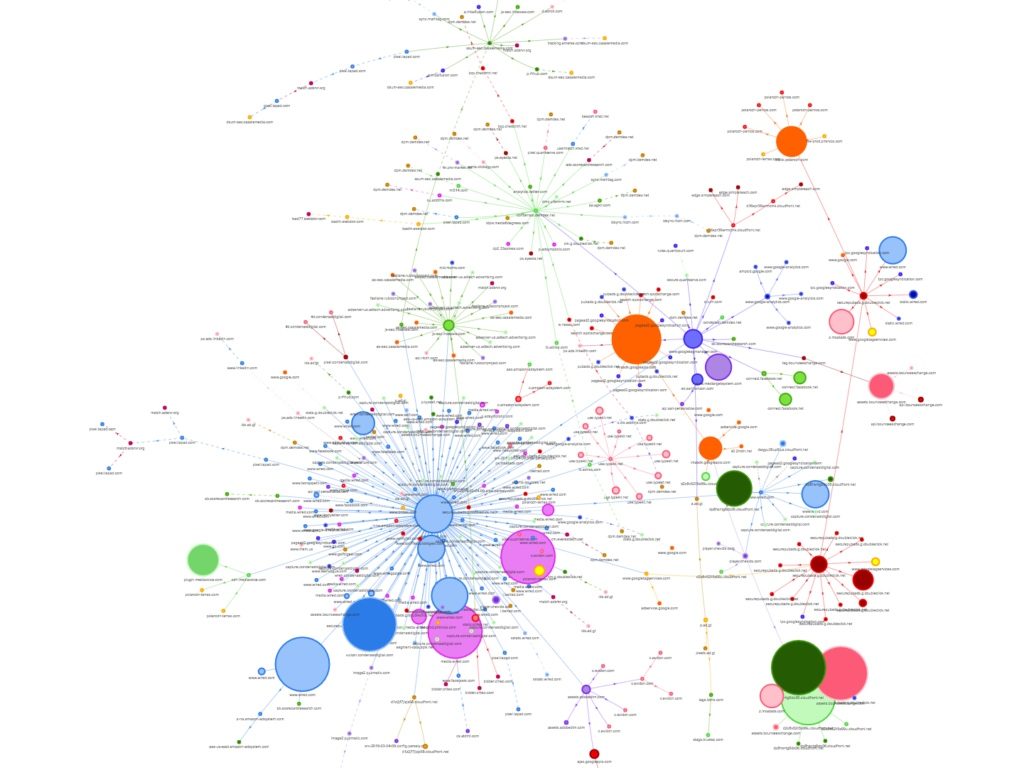

So when I make use of a third party service, thousands of miles away, run by a group of people I don’t know, possibly from a different culture with very different laws & values, what control do I really have over their actions? What’s more, some third parties hand off functions to others, multiplying the spread of data, and this can get out of hand very easily. Here is a request map of wired.com’s home page, showing requests for the home page itself (that big blue star in the bottom left), and they the myriad connections to third parties – some entirely innocent, other perhaps not so:

If I am a data controller, I am responsible for the actions of every single one of these third parties – it’s difficult enough being responsible for the security of a single site, let alone hundreds. That’s an awful lot of liability for a company to put so little effort into controlling.

When personal data is handed to a company, I want to know that it is safe and being used only to facilitate my transaction with them, or I want to be able to check the third parties to see if I feel they are trustworthy – because it’s my data, and thus I want control over it. Many sites fail to reveal who these third parties are, or there are so many that I could spend years doing due diligence – made even more impossible by the moving target that is the list of third parties. So when a company says they “take your privacy seriously”, and at the same time shares data with “trusted third parties”, don’t believe them. How many fines and breaches does a company need to get before they are no longer considered “trusted”?

While there has been much fuss around GDPR, the fundamental principles of data protection laws have not changed in decades – there is probably an 80% conceptual overlap between GDPR and the UK’s data protection act of 1984, so anyone expressing shock at GDPR was probably doing something pretty bad to start with.

Of course, there is a reasonable solution: work with companies where you can check their track record, that has a policy of transparency, that avoids unnecessary third parties, where you can meet the people involved (at least virtually!), build a relationship with them, and make a personal judgement of whether they can be trusted to keep your customers data safe.

We are trying to achieve that. Don’t believe us? Well, here’s our privacy policy…